What makes this agreement quite significant is Beijing’s willingness to shed its image of a silent power and go beyond its usual emphasis on pursuing its economic interests to not only actively encourage détente between two regional hostile powers but also but bring them on the table and get them to sign an agreement “to resume diplomatic relations between them and re-open their embassies and missions within a period not exceeding two months”.

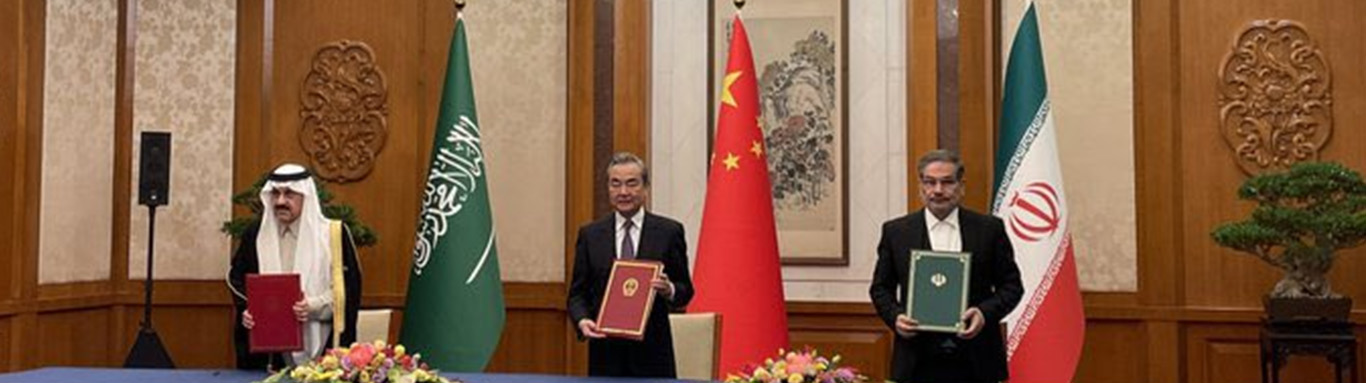

On 10 March 2023, a joint trilateral statement of China, Iran and Saudi Arabia announcing the détente between Riyadh and Tehran took the international community and experts by surprise. This reconciliation is an important event in today's Middle East, not just because the two regional belligerent powers have announced a thaw in their acrimonious relations but also because of China’s role in brokering this. While occasional reports appeared about the back-channel engagements between Riyadh and Tehran facilitated by regional actors like Iraq, China’s role in brokering the deal came like a bolt from the blue.

The statement declared that the two countries reached an agreement “to resume diplomatic relations”, “reopen their embassies and missions”, and “their affirmation of the respect for the sovereignty of states and the non-interference in internal affairs of states.” What is prominent in the statement is its acknowledgement of the role played by China in this reconciliation process, crediting it to “the noble initiative” of President Xi Jinping and “China’s support for developing good neighborly relations.”

This might look like a diversion from the usual diplomatic line Beijing has taken so far in the Middle East and elsewhere, where it has maintained a strong economic presence and a studied distance from local and regional politics what was believed to be a delicate balancing act. As this author had argued elsewhere, given the growing dependence of Beijing on Middle Eastern energy for sustaining its economy, it was only a matter of time before it would push for its political involvement and shun its balancing approach, something substantiated by its role in brokering this agreement. However, this is not to suggest that China had not previously attempted to ease the tensions between these two states. Earlier, when Iran-Saudi relations went south in 2016 following Riyadh’s execution of its Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr and the subsequent torching of the Saudi embassy by Iranian Shia protestors in retribution, China attempted to defuse these tensions by dispatching its Vice Foreign Minister Zhang Ming to Riyadh and Tehran subsequently, while asking “the relevant parties maintain calm and exercise restraint, step up dialogue and consultations and jointly promote an amelioration of the situation."

Interestingly, President Xi Jinping followed Zhang Ming’s visit with his tour of the two belligerent states as part of his three-nation visit during 19-24 January 2016, including Egypt, raising speculations that Beijing was going beyond its courtesy calls for maintaining peace in the region. However, neither of the visits led to any tangible thaw between Riyadh and Tehran, as they continued their hostilities with no diplomatic representation in either country. China did not involve itself further in brokering peace between these two claimants for leadership of the region and the Muslim world.

China has insisted on maintaining an economic profile in the region to guarantee its energy security. In 2020-21, China’s exports to and imports from Saudi Arabia touched $ 31.8 bn and $33.4 bn, respectively, with a cumulative bilateral trade of $65.2 bn. Being the largest crude petroleum supplier, Riyadh’s exports to Beijing majorly included crude petroleum worth $24.7bn. In 2022, the kingdom shipped around 87.49 million tonnes (equivalent to 1.75 million bpd) of crude to China. Likewise, China’s exports to and imports from Iran were $8.51 bn and $5.85 bn, respectively, in 2020-21, with Beijing featuring as Tehran's largest bilateral partner for years. A Reuter’s report claimed that the Asian economic giant sourced over 1.2 million bpd in 2022 from Iran. Together, as the above figures signify, the two countries export a significant volume of hydrocarbon to fuel the economic wheel of the People’s Republic of China, which only increases the import of the region in Chinese calculations.

What makes this agreement quite significant is Beijing’s willingness to shed its image of a silent power and go beyond its usual emphasis on pursuing its economic interests to not only actively encourage détente between two regional hostile powers but also but bring them on the table and get them to sign an agreement “to resume diplomatic relations between them and re-open their embassies and missions within a period not exceeding two months”. By agreeing to remain party to the process of reconciliation which is likely to pan out in the coming days, China has also baited its reputation on the future of this agreement.

This is important because Saudi Arabia was seen as the country spearheading anti-Iran political front in the region and internationally even in cohort with Israel, encouraged by the US. Its current leadership, led by Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman (MBS), played an important role in influencing President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from the multilateral Iran nuclear deal (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action-JCPOA) in May 2018. Consequent to the arrival of President Joe Biden, Washington’s approach towards Tehran had witnessed a shift, with the two sides restarting their engagements to revive the JCPOA. This appears to have influenced the decisions of the Saudi leadership to tone down its anti-Iran rhetoric and seek peace with its regional arch nemesis.

There were multiple reports that the two sides engaged in backchannel diplomacy to restart their relations with the “special efforts” from former Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi during his premiership between 2020-22. This was halted reportedly as recently as by December 2022 because of strong-government protests in Iran following Mahsa Amini’s killing, allegedly at the hands of the Islamic Republic’s moral police, wherein Tehran accused Riyadh of a role in encouraging and inciting protests. In addition, the change in leadership in Baghdad also appeared to have played its part in stalling these engagements. However, what nobody noticed was the backchannel efforts by China to encourage these two states to restart engagements resulting in the current agreement. Michael Kugelman, an American foreign policy expert, called this a “surprise” and “watershed for” international relations of the Middle East. “This China-mediated Iran-Saudi Arabia reconciliation is a black swan event-- a surprise, a rare watershed moment for international relations that'll have major ripple effects across the globe, including South Asia-especially Pakistan-where Iran-KSA rivalry has played out heavily,” Kugelman wrote.

This is being hailed as ‘coming of age’ for China in the region and at the international level, where it has previously hesitated to involve itself politically. It signifies the confidence that Beijing has acquired about its role in Asia and at the international level, where it sees itself as a major global actor at par with the US, if not above it, and certainly not below it. At the same time, China would love to project its role also as an indicator of the rise of Asia and receding of the American and European power in the region. Similarly, the confidence of these Middle Eastern regional giants in Beijing’s capability to take guarantee for their concerns, is also another important take away from this agreement. Is it true that the hands are off the gloves for Beijing now? It would be intriguing to see whether it would continue with its newly assumed political role in the region, or revert to its role as a quiet economic actor.

At the same time, in the context of regional realignments, it would be interesting to see how would Saudi-Iranian normalisation affect the covert Saudi-Israeli engagements, which had, at their core, their mutual anti-Iranian sentiments. There is a belief that this thaw would have a positive ripple effect regionally, and the countries that have hesitated to join either of the two in their competition for regional heft would now have a breather. As Trita Parsi, an Iranian-American expert, voiced, the “Saudi-Iran normalization is a BIG DEAL, not just because of the positive repercussions it can have in the region - from Lebanon to Yemen - but also because of mediated it (China) and who didn't (US).”

Additionally, it appears highly likely that the nuclear negotiations to revive the JCPOA may now inch towards completion, something that would help bring Tehran into the regional mainstream. It is important to note that China is a signatory to the JCPOA and seeks revival of the deal, wherein Riyadh had voiced strong reservations and fears about Tehran pursuing a nuclear programme for military uses. Therefore, should this détente result in Saudi concurrence to revival of JCPOA, it would be worthwhile to see how that would affect the international oil market. These two states have traditionally adopted contrasting policies in their OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) dealings. Riyadh has conventionally sought a long-term market capitalisation. In contrast, Tehran sought short-term profits to fuel its shagging economy because of international and US sanctions for its suspected nuclear dealings. Concomitantly, as China pushes its Yuan currency for international trade, it would be interesting also to see if this could result in Riyadh deciding to shift its bilateral trade with Beijing using the Chinese currency at the cost of the US dollar.

* Dr. Mohmad Waseem Malla is a Research Fellow with the International Centre for Peace Studies (ICPS), New Delhi. He has a doctorate from the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India. He is a keen observer of the Persian Gulf and South Asia developments and China’s rising profile in the Middle East.

Comments